Does academia think markets are less predictive than polling?

In his morning column, Stephen Bush wrote: “The academic literature is also very clear. Betting markets are less predictive than polling, write Robert Erikson, political scientist at Columbia University and Christopher Wlezien, Hogg Professor of Government at the University of Texas at Austin.” (FT ($)).

On reading this I was fairly conflicted:

I like Stephen Bush, and tend to believe him

I do think betting markets are sometimes less predictive than polling (read broadly)

I doubted that the academic literature is ‘clear’ on this

As commenter Legal Tender pointed out: “I don’t think a ten year old study is the last word on polls.”. Quite. Indeed, even at the time, the topic was contentious.

One dissenter, Justin Wolfers, an economist at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania who has done extensive analyses of prediction markets, criticized Erikson and Wlezien’s results, saying that their study only compared a few elections and polls. Wolfers also objects because the 2005 analysis “adjusts polls but doesn’t make a corresponding adjustment of prediction markets.”

I decided to have a ‘quick’ skim of the literature, and see what I could find.

tl;dr - Academics are undecided, but regardless, Stephen Bush is wrong here.

The Story so far…

My search unearthed about 30 studies relevant to the topic. Starting in ~2000 through to the present day. I’m going to summarise a few of the papers and their results.

The earliest empirical papers on the topic of prediction markets are based around Iowa Electionic Markets (IEM henceforth). IEM is very similar to PredictIt, in that it’s a political prediction market, masquerading as an academic project, run by academics, for small stakes. Those papers were written by a group of academics (Berg, Nelson, Forsythe, Rietz being the most frequent) who were mostly involved in the project. Their main results (a) are based around comparing polling averages to vote share markets and showing that the average errors for the vote share markets are lower:

(Look at the furthest right bars to see an average, polls are higher than both election-eve markets and last-week markets)

In their other papers, they have looked at polls vs markets earlier in the cycle. (Markets tend to do better, but I’m a little leery of the metric that they consider (as well as other issues which later authors raise)).

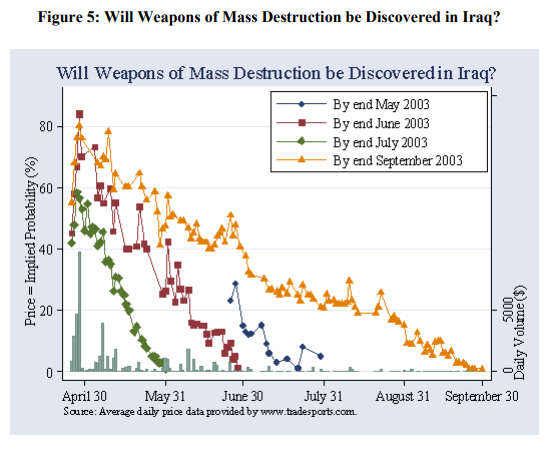

A variety of other authors then took those results and requoted them over the following years. One of the better papers in this vein is Wolfers and Zitzewitz (2004) which talks about prediction markets in general. (Minor digression) It contained market on whether or not WMDs would be discovered in Iraq:

So far (~2007) I would summarise the academic consensus as being pretty clear: “Markets are better than simple polling averages”. The data was almost entirely sourced from IEM, and the methods for handing both IEM data and polling data were fairly rudimentary.

At this point, Stephen Bush’s academics come out swinging with their paper Are Political Markets Really Superior to Polls as Election Predictors? (2009).

We then show that when poll leads are properly discounted, poll-based forecasts outperform vote-share market prices. Moreover, we show that win-projections based on the polls dominate prices from winner-take-all markets.

Their logic resolves around adjusting polling averages for the US presidential elections between 1988 and 2004 (n=5) and comparing the performance of both the vote-share markets and the winner-takes-all market. They make a fairly convincing case that we should normalise the polls in a few ways, based on their historical performance. (Fade leads, especially when they are the out party, don’t trust poll-reported margin of errors). (All of this should be very familiar to people who follow Nate Silver)

On the other hand, they claim that their model out-performs the winner-takes-all markets.

A quick look at their performance, and I know which model I’d rather bet against. (Hint, it’s the one which is crazy volatile).

One final thing to note, despite all of this:

The market price is superior to a naïve reading of the polls.

(I will come back to this later).

David Rothschild then steps into the ring to adjudicate the situation. He essentially does similar (but better) analysis to Erikson and Wlezien. His improvements include:

looking at a wider list of races (n >> 4/5 presidential markets, although still correlated markets)

substantial improvements to Erikson & Wlezien’s winner-takes-all estimate

‘debiasing’ prediction markets (essentially adjusting very odds-on races where the documented ‘long-shot’ bias rules)

He concludes that:

‘debiased prediction markets’ > good polling modelling > ‘prediction markets’

I think it would be fair to add “but the differences aren’t massive”.

From this point forward, the academic literature becomes primarily interested in a question closer to “are prediction markets better than Nate Silver?”. This is, of course, a good question, which I might come back to at a later date, but it’s not super relevant to my original question.

Arnesen and Bergfjord used the Erikson and Wlezien methodology for the 2008 and 2012 US Presidential elections and found that prediction markets outperformed there.

Vaughan Williams and Reade used their own statistical model for polls and to look at the 2008 US Presidential election, and found that prediction markets outperformed them

Lauderdale, Hanretty and Vivyan weighed in with their own model for the UK General Election in 2015. The market marginally outperformed them, but I think the fairest decision is a tie.

There are no academic papers which manage to aggregate polling data (post Erikson’s 2009 paper) and beat the market, although The Economist’s model was both open source and had an academic paper published about it which did beat PredictIt, so it will be interesting to see how those perform going forward.

… and how I read it

My main conclusions are (and expect me to change my mind on this going forward):

Academia is in relative agreement that prediction markets are better than raw polling data

Academia has failed to build models that aggregate polling data to consistently beat the market

Prediction markets have some systematic biases (long-shot bias being the most common) and adjusting for them improves their forecasting ability

It is unclear whether or not Nate Silver outperforms prediction markets, but it’s probably close enough that it’s too early to say

Probably my clearest conclusion is:

If you don’t know how to aggregate polling data yourself, and Nate isn’t doing it for you, you should trust the betting markets

One topic which I didn’t really address in the above (although it is an important example of how prediction markets are better than polling) is the speed in which they react to news. Stephen Bush mentioned it: “[…] if you want a sense of who is “winning” a televised debate, the direction the betting odds are shifting is a useful bit of additional information — albeit one that will most be rendered obsolete by post-debate polling.” but I think this understates the story. Take the televised debate Stephen Bush was nodding at.

During the debate - betting markets: “Truss, Truss, Truss”

Snap polling after: “… maybe draw?”

The next day - “Truss was better”

Doesn’t seem clear to me I learned more waiting for the polling than from the prediction market. (And even looking at the viewer polls, it doesn’t give me a good idea of how much to update my expectations).

Papers for the interested

Forecasting the Vote: A Theoretical Comparison of Election Markets and Public Opinion Polls

Comparing prediction market prices and opinion polls in political election

Are Political Markets Really Superior to Polls as Election Predictors

Forecasting Elections: Comparing Prediction Markets, Polls, and Their Biases

Consistency in the US Congressional Popular Opinion Polls and Prediction Markets

Do polls or markets forecast better? Evidence from the 2010 US Senate Elections

Markets vs. Polls as Predictors: An Historical Assessment of US Presidential Elections

Prediction Markets vs Polls - An Examination of Accuracy for the 2008 and 2012 US Elections

A comparison of forecasting methods: fundamentals, polling, prediction markets and experts

Forecasting Elections: Do Prediction Markets Tells Us Anything More than the Polls?

Polls to Probabilities: Comparing Prediction Markets and Opinion Polls

Forecasting Federal Elections: New Data From 2010–2019 and a Discussion of Alternative and Emerging Methods